The Search for Auto-Loaded DLLs and Windows rpath

Edit: I added a section about delayed loading thanks to comments which pointed out that I had overlooked this

There are two ways of loading a shared library (.DLL on Windows, .so on most Unix platforms, and .dylib on macs). One is to use a function like LoadLibary or dlopen. Then you must manually extract the functions from the library with GetProcAddress or dlsym. Most linkers (all that I know of) also allow you to link with a shared library so that it’s loaded on startup and its functions are automatically resolved to symbols in your code. That’s particularly useful as it’s the only sensible way to load a C++ interface from a shared library.

The first way (the manual one) works almost the same way on all platforms. You can supply a path to the shared library file, either a relative or an absolute one, and it will work. I’m going to discuss the second way of loading shared libraries: the automatic one. There is a critical difference between how it works on Windows and other operating systems, namely, the way in which the executable1 searches for the shared library file to load.

If you’re a Windows-only programmer, you probably developed your own way to deal with DLL Hell, whether it’s by redirection or careful output directory management. Or, you know, alternatively, you try to use DLLs as little as possible. Anyway, you should know that on other operating systems when linking with a shared library (.so or .dylib file), you can supply a search path for it to the linker itself. In fact, to some people’s occasional frustration, the default search path when linking with no specific arguments is the absolute path to the shared library. This search path is called an rpath.

If you do multi-platform programming, you’ve probably experienced frustration with the lack of rpaths on Windows.

If you’re not a Windows programmer, I don’t know why you’re reading this article, but to put it simply: In Windows, shared libraries, or DLLs, don’t have rpaths. Instead the executable searches for a shared library by filename in a variety of places which you cannot control when building the executable. It searches the files in the same directory as the executable, then files in your PATH environment variable, and some other insignificant places. And if the DLL isn’t there?…

Why do we want that on Windows?

Some may be wondering why one would want such a thing. I’m sure some are perfectly content with the DLL search order, but here are two very popular use-cases2:

Using third party libraries

This is probably the most common case. You want to use a third party library, but you don’t really want to build it yourself, so you download a handy binary release and extract it… well, somewhere. Or you do want to build it yourself, but you do it with its default settings and it spits out its binaries again somewhere.

Most Windows programmers are likely familiar with this scenario.

Using CMake (or anything other than .vcxproj, really)

CMake is the de facto standard for building C and C++ software these days. Most open source C++ projects use it. Of course there are many alternatives and most of them work the same way: the default output for a target is likely not the same for all targets3. So, when you build a project which outputs DLL files, by default it’s very likely that not all DLL files and executables will end up in the same directory.

I suspect that most Windows programmers who use a build system (or a build system generator) other than Visual Studio’s .sln and .vcxproj files are familiar with this scenario as well.

What do people do?

Given that this is a pretty popular issue in Windows development, there are already popular solutions to both use cases, each with its own downsides compared to rpath.

Change the output directory

This is probably the most popular solution for the case where you have a project which outputs executables and DLLs. You just manually change the output directory for all targets to be the same. In CMake you will often see people changing CMAKE_RUNTIME_OUTPUT_DIRECTORY to something4. This sets the output directory for all executables and DLLs to be that something.

Many projects use this. I use this. As a whole it’s a relatively safe and often adequate solution5. There are some cases, however, where a common output directory is inapplicable:

- Having multiple targets which produce binaries with the same name. It’s impossible to have them in the same directory.

- Creating some configuration files with the same name. With CMake this can happen when you have files which depend on generator expressions which may be placed in

$<TARGET_FILE_DIR>. In any case configuration files whose name doesn’t depend on the executable name will clash. - Same goes for output files with generic names, like

output.log.

These are indeed very rare and some people might even say that they are bad practice and should be avoided. However, if something like this does happen, it can very well be missed which can lead to subtle and hard to detect bugs.

Copying DLLs

When dealing with third party libraries, you typically don’t have such fine control over where their DLL files end up, so copying them alongside your executables is often the choice. This is probably the most popular solution for third party libraries. It’s employed by many existing package managers. This requires a common output directory6 and carries with it the drawbacks of having one, but it’s also wasteful, having multiple copies of the same files over and over again.

To avoid this waste there’s another popular approach here and that is copying or installing third party DLLs to some directory in your PATH. This fixes the problem of filename clashes, but introduces a new one: the so called DLL Hell. DLL Hell is when you have multiple DLLs with the same name in your PATH. Executables will automatically load the first one which matches, but that may not be what you want. There might be differences in version or Debug/Release differences. Such problems are hard to detect and often lead to crazy behavior or, worse, subtle and hard to detect bugs. There is a way to deal with that on Windows (I mentioned redirection manifests above), but it requires you to have control over the DLLs as opposed to the executables. If a third-party vendor doesn’t support redirection manifests, it may be really hard to add them on your own.

What else can people do?

Having a common output directory and copying third party dependencies to it mostly works. It’s what almost everyone does. But I don’t like it. And neither should you!

Manually taking care of this is iffy and error prone. Knowing how easy it is to just specify a search path for a shared library on other platforms makes me cringe every time I have to deal with this Windows-specific problem.

I decided to do some research and try to find a solution. Here’s what I found:

(Useless) application configuration files

One of the first things I found in my research were application configuration files. At first glance it seems like the ideal solution: You add a manifest to the executable, you add a configuration file, and in it you specify search paths for DLLs. Voilà! Rpaths on Windows.

I was so impressed by this that I began envisioning a CMake library which would take care of this automatically. I thought of the interface, how it would work… and then it dawned on me to ask myself why there isn’t anyone already doing it. Sure, it seems like a somewhat obscure feature, but someone had to have thought of this.

My second glance explained why this isn’t a solution. See, in the linked docs they talked about assemblies. Windows documentation used to use the term “assembly” quite loosely before, but it has been mostly improved to mean exactly one thing: .NET binaries: .NET executables and .NET DLLs.

If you program managed binaries, this might be useful info to you (and most likely you already know this), but I work mainly with native binaries. I suspect most readers do, too. So, yeah… this really got my hopes up, but sadly it does nothing to native binaries.

Registry “App Paths”

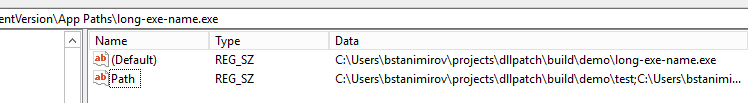

There’s this thing called App Paths. In your registry under HKLM or HKCU you can find Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\App Paths\ which contains a list of applications that can be started from the Run (Win-R) window without specifying a full path. If you open this, you will probably find your browser, your video player, and similar default programs inside.

You can add your own, though. Just add a new key with the name of your executable (say “myexe.exe”), then in the default value supply the actual path to that executable. In doing so you will inform the operating system that an executable is globally available to run. Now you can run without the full path to the executable via the Run window, by calling ShellExecute.

The important thing here is that Windows will also load another value from the registry key of your executable. It’s called “Path” and in it you can supply a string which will be appended to the PATH environment variable when the executable is started. So in Path you can add directories which contain the DLLs you need.

Like this

This will work.

…when you run it from the Run menu.

…or when you start it from another program, by calling ShellExecute.

…even when you double-click it in Windows Explorer.

…but crucially and to my great annoyance NOT when you run it from the command line and NOT when started from Visual Studio with F5 or ctrl-F5.

Well, technically you can start it from the command line by typing > explorer myexe.exe, or if you create you own “starter” program which forwards all arguments to ShellExecute, but both will open a new window. This means the standard output of your executable will not be in the console window you started it from. Also, if you want to debug it from Visual Studio, you can manually attach to the process. It’s not impossible to work like this.

Not to mention that this is pretty hard to automate. You have to play a lot with the registry as part of the build process. Not so nice. Oh, and if you have multiple executables with the same name or you want to use this for DLLs, you’re also out of luck.

This info is useful for Windows application development, of course, but I’m sure those who do that are already familiar with this. As a solution to our rpath problem, this is not very practical.

Visual Studio specific: Custom .user file

So App Paths doesn’t help us when we run executables from the console or from the IDE. This reminded me that there’s a much better development alternative if you’re like me: you use Visual Studio and 99% of the time you start your executables from within it with F5 or ctrl-F5 instead of from the console or otherwise.

Visual Studio allows you to set a custom environment for a project when you start it from the IDE. It’s in project Settings>Debugging. The important thing about the Debugging settings is that they’re not stored in the .vcxproj file, but instead in an associated .vcxproj.user file. This file is not touched by the popular .vcxproj generators like CMake, so you can actually generate it yourself.

Here’s an example:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<!-- Template configured by CMake -->

<Project ToolsVersion="@USEFILE_VERSION@" xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/developer/msbuild/2003">

<PropertyGroup>

<LocalDebuggerWorkingDirectory>@USERFILE_WORKING_DIR@</LocalDebuggerWorkingDirectory>

<LocalDebuggerEnvironment>PATH=@USERFILE_PATH@;%PATH%$(LocalDebuggerEnvironment)</LocalDebuggerEnvironment>

<DebuggerFlavor>WindowsLocalDebugger</DebuggerFlavor>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>

Then from CMake you can configure it with something like:

if(MSVC)

set(USEFILE_VERSION 15.0) # Visual Studio 2017, use MSVC_VERSION

# to properly set this variable

# (it's not in the scope of the article)

set(USERFILE_WORKING_DIR your\\working\\dir) # windows paths

set(USERFILE_PATH path\\to\\lib1;path\\to\\lib2)

configure_file(

"UserFile.template.user"

"${CMAKE_CURRENT_BINARY_DIR}/${YOUR_TARGET_NAME}.vcxproj.user"

@ONLY

)

endif()

I’ve used this on a couple of occasions. It can actually make your life a bit easier if you always start the program from Visual Studio in development.

But I digress…

Patching the executable

At this point I had to admit that the operating system wasn’t going to help me. Then I thought something along the lines of the following:

What does automatically loading a DLL actually mean? To load a DLL you have to call

LoadLibraryin some way or another. So the linker must produce some code which callsLoadLibrary("mydll.dll");and then updates the symbols I use from this DLL to the correct addresses.

This of course means that the executable contains the raw string "mydll.dll" somewhere inside it. What if instead of this it contains "C:\mydll.dll"?

This seemed like an easy-to-have revelation, so I searched for something on this subject and quickly found this blog post by Max Bolingbroke.

In short, here’s what he does:

- Build executable which links to some DLL.

- Open the executable with a binary editor, find the name of the DLL and change it to a full path.

- In case there is not enough room for the full path, you can either create

a_dll_with_a_really_long_name_which_will_be_replaced_by_a_full_path_to_a_dll_with_a_shorter_name.dll - Or patch the linker .lib file with dlltool.exe:

dlltool --output-lib library.lib --dllname veryverylongdllname.dll library.oonly to replace the longer name with your full path with the binary editor afterwards. - Or if you’re using a .def file, you can specify the long DLL name in it.

- In case there is not enough room for the full path, you can either create

- That’s it. You hacked yourself an rpath for the DLL on Windows.

Do check out the blog post. It contains the whole process. It’s made with MinGW, but I was able to replicate his results with executables created by msvc as well. In fact, I created a small (and naïve) command line utility which can be used to patch an existing executable or DLL according to the strategy from above. It works for binaries produced by MinGW or msvc.

Yes. This really works. The problem is that automating it is indeed a bit of a pain. You have to patch executables after they’re built and this really confuses your build system. I suspect that using my tool or a similar one, an automation is possible (though likely build-system-specific), but still, it’s patching executables as a post build step. It’s definitely something which is frowned upon in C and C++ circles.

I therefore wouldn’t recommend this strategy over single-output-directory-and-third-party-dlls-copies, but if you’re pressed to have the closest possible thing to an rpath on Windows, this really seems like the only way. I for one will definitely keep it in mind in case I ever have to use it.

Visual C/C++ specific: delayed DLL loading

Microsoft’s linker LINK.exe supports delayed loading. This feature allows a linked DLL to be loaded when the first call to a function from it is made instead of at the startup of the executable. To make use of delayed loading you should add the /DELAYLOAD:dllname switch to the linker command (for example /DELAYLOAD:foo.dll).

At first I didn’t realize how this can help. After all, I don’t care when the DLL is loaded but where it’s loaded from. But after some comments to this I found out that I had neglected to see ways to make this actually quite useful.

First there’s the naïve (and quite dangerous) approach which you should probably not use: SetDllDirectory. This function allows you to set the search path for DLLs which LoadLibrary will use. This will probably work for the simplest of cases, but there are some problems which would make it from unusable to dangerous:

- If you call functions from a DLL globally, this will not work. You have no way to guarantee that

SetDllDirectorywill be called before your global calls7. SetDllDirectorysets the search paths for the entire process. This means that these search paths will be used for all calls toLoadLibrary. Depending on what kind of DLLs you have on your system, this may actually lead to stuff being loaded which you don’t want and bring you to a whole new level of DLL Hell.

There’s another approach, though. Using the delayed loading helper function.

In a typical delayed loading scenario (where you only care about when or if some DLLs are loaded) you would link with Delayimp.lib which provides a function to do the actual delayed loading. You must define a hook function which the helper function will use. The hook function is quite easy to use and actually allows you to substitute the call to LoadLibrary with your own. You can see how to do so in the docs. You would also see that setting the delayed loading hook depends on initializing a global variable, which brings us back to the problem of using functionality from the DLL globally. You will need this global to be initialized first, but you will have no way of guaranteeing it7.

The thing is that you could choose to not link with Delayimpl.lib and instead provide a delayed loading function yourself. Now this is not trivial but it seems to be possible. I will probably play around with this in the following days and update this article.

Using delayed loading with a custom helper function seems to be the closest thing you can get, without patching the executable. Still, there are several obvious problems with it which make it unpleasant:

- It is LINK.exe specific, so Visual Studio specific. No MinGW here.

- You will have to include a significant platform-specific piece of code in every binary

- Your build system will have to supply the paths to libraries to the compiler. This is not really that trivial, because you will somehow have to transfer the knowledge of what DLLs you are using to the compiler. The easiest solution here would probably be for the build system to configure some .c file which will be added to the binary.

Nevertheless this does seem quite workable, and as I said I will play with it more.

What would be really nice?

As you can see, sadly none of the solutions above are ideal. There is simply no great alternative to rpath on Windows, even though thanks to delayed loading we could manage it somehow, and thanks to Max Bolingbroke we learned how to hack it in. But from learning how to hack it in, it seems as though it’s not that hard to actually have a solution. The linker could easily do it for us. In fact you saw that dlltool.exe gets us halfway there already.

So here’s my appeal to people who write linkers for Windows:

Can we have a way to specify paths for DLLs?

Micosoft, can we have this for LINK.exe?

/RENAMEDLL:"foo.dll","c:\foo.dll"

Mingw-w64, can we have this for ld.exe?

--renamedll "foo.dll" "c:/foo.dll"

Please?

-

By executable here I mean an actual executable or a loaded shared library which wants to load another shared library. In a sense both are executables, so I’ll just use this word to refer to both cases. ↩

-

And perhaps many others which I haven’t thought of. ↩

-

For CMake the output path of a target depends on the path of the

CMakeLists.txtfile which created the target, relative to the rootCMakeLists.txtfile. ↩ -

A popular “something” here being

${CMAKE_BINARY_DIR}which is where the build files are generated ↩ -

Minor inconveniences may exist. One worth mentioning would be that for ctest from CMake you have to manually set the executable path for each test. Like:

add_test(NAME ${test} COMMAND $<TARGET_FILE:${test}>)↩ -

Well, actually, not necessarily. You can copy files many times next to specific dependencies, like if you have

dir_a\a.exeanddir_b\b.exe, you can copy third party DLLs in bothdir_aanddir_b. This is even more wasteful. ↩ -

At least not unless you have a single compilation unit or manually patch the executable as a post-build step. I’m not aware of LINK.exe supporting linker scripts to let you manually reorder the executable sections when linking. If it does, this could also make it possible to guarantee something is executed first. ↩ ↩2

Leave a comment